Johannesburg based photographer Andile Buka is the very first photographer/ bookmaker that has been interviewed exclusively for Africa in the Photobook by Ben Krewinkel. His first book, the beautiful Crossing Strangers was published in 2015 by MNK Press and explores ‘the landscape of Johannesburg, the people who both inhabit and fill its city streets’.

BK: Andile, thank you for having this interview. Can you explain the main themes you explore in your book Crossing Strangers and can you let us know where the title came from?

AB: The book was very much process-based, rather than an exercise in trying to illustrate a pre-determined theme. When I first starting shooting on the street, I had a medium format camera. I couldn’t use this for point-and-shoot work, but not having a studio didn’t pose a problem. I had the express urge to use the camera in a way that it wasn’t normally, outside of the studio environment.

I would wake up, walk, go to Soweto, walk, go to my parents’ area, walk. It took me a long time to actually get up the courage to photograph someone, a stranger – at least a few weeks. But after developing the first few rolls I gained confidence. The people and things that I took picture of were simply those that I was drawn to in the moment. They weren’t a particular age, or particularly fashionable; there was nothing specific about them, just something that caught my eye.

Initially the pictures weren’t very good, but somehow these sessions became a weekly thing. The title came to me in the early days of “Hi, how are you? Can I take a photo?”. It was the process of literally crossing paths with unknown people and places, and making a record of these encounters: crossing strangers.

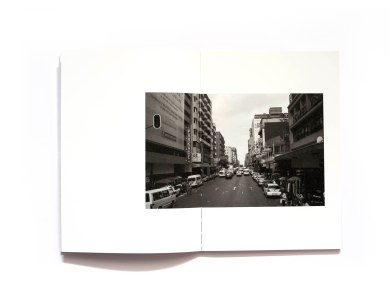

BK: In your book you combine portraits with cityscapes. How are those connected?

AB: Many people, because of the city’s history, neglect to experience the city from various physical perspectives. That is how two residents can both live here, but not really be navigating the same city. When you look at the city from the vantage point of a building, you mostly see the cityscape – the people at a remove on the street below. You need to actually walk on those streets in order to properly see the people.

Furthermore, the buildings here have faces that change very rapidly. There is “rejuvenation” in the city, but also a wealth of hijacked buildings. You can walk past a busy, prosperous building, and two weeks later it’s abandoned. Or vice versa. These changes have vast implications for the people living and visiting Johannesburg. The vagaries of these kinds of interactions between buildings, people, and city are at the core of my work.

BK: You write in the very short introduction that you are ‘presenting spaces that are unfamiliar and unnoticed.’ Unfamiliar and unnoticed to whom?

AB: Primarily to myself. There were places in the book that I was already familiar with, but I went through the process of re-investigating them through taking these photographs. Especially when I would revisit sites at different times of day – for example the taxi rank – they would change drastically from morning, to noon, to evening. Further to that, in a general sense, there is a perception that Johannesburg has been documented many times. I don’t really subscribe to that. Joburg doesn’t really exist in a fleshed-out way in the European or Asian cultural consciousness, as was evidenced by the reception of the work on other continents.

BK: There is not a lot of text in the book itself, just a short introduction that presents us Johannesburg as a city full of contradictions, structured to it’s past, but continuously built towards it’s future. How did you use your photography to show the reader these contradictions and what are those contradictions?

AB: There is a conflict between our understanding of the (real) danger that exists within the confines of downtown Johannesburg, and the fact that the majority of people who frequent that area live important and worthy lives under those conditions.

As a resident, who himself lives and works within these areas, I have a strong sense that Johannesburg is the kind of city that “sees” you. It’s the City of Gold. The reward for hard work and hustle is no longer gold but opportunity, and one feels as though if you work hard the city will notice you. My photography is a way of looking back at the city. I am not interested in glorifying the nobility of living within harsh conditions or amongst crime. Instead I focus on recognizing the value of the way of life that gentrification and development is, at once, improving, and erasing.

BK: Crossing Strangers comes with a loosely inserted essay by Rangoato Hlasane titled Monuments to the eternal spaces. Can you tell us how you got involved with Rangoato Hlasane and how his essay is connected to you project Crossing Strangers? I ask this since to me the text seems to be more explicitly ‘political’ than the book itself (though I can be wrong). Especially the last paragraph in his text which reads: ‘[…] One thing is for sure, the children of white supremacy are back in the ‘inner city’ only because the like the idea of Joburg […]’

AB: Although it is not explicitly political, I would assert that the photographs within Crossing Strangers implicitly carry a strongly political message. There is some rigidity, even within the arts world, as to what constitutes political work. One often comes up against the idea that if photography isn’t documenting particular social ills – Poverty or social ills for example – that it doesn’t have a political statement to make. With this in mind, the publisher and I sought out an essayist who would explicitly articulate an understanding of the city that would align with my own. Rangoato’s writing reflects my daily experience as a resident of Johannesburg. I too, have seen people coming in from the north to sit on a rooftop and sip margaritas, taking with them, on their speedy return to the suburbs, a very limited understanding of the city. I don’t carry resentment towards people like this, by the way, but it bears recognizing the limitations of that experience of downtown. So, while Rangaoto’s take is bluntly put, it is not far removed from my own.

BK: I can imagine Crossing Strangers can be confused with many other ‘City Books’ by street photographers. I suppose the book is far more ‘political’ than many of those. Is it, according to you, possible to exclude the past when making a book on Johannesburg? Why?

AB: It’s completely impossible to exclude the past when making a book about Johannesburg. The people that Rangaoto talks about in his essay – mainly white, coming in from the north – are, frankly, afraid to interact with downtown from any other vantage point than a rooftop bar. But historically, during Apartheid, the CBD was primarily dominated by whites. So, with this reversal, those using the CBD now are living and working in spaces that for decades they were unable to set foot in. To add another layer of contradiction, the buildings are still largely owned and profited from by white people. It’s a complicated physical and social landscape, that cannot be viewed but through a political lens.

BK: Can you tell us how long it took to produce all the body of work required for the publication?

AB: I started the project June 2014 and completed it July 2015, so roughly one year.

BK: Is there a specific reason why your work Crossing Strangers was shot in black and white, since you often, also in your personal projects, work in colour?

AB: Actually when I first started photographing strangers I was working in colour. It was purely an artistic and aesthetic decision, made jointly by the publisher and me in January 2015, that I would work in black and white for this publication.

BK: South Africa has always been Africa’s main producer of photobooks. What do you think about the current production of photobooks by South African artists?

AB: The photobooks coming out of South Africa at the moment are being produced by my contemporaries – they are very youthful. For a long time the photobook market here has been dominated by old-school photographers. Younger artists are increasingly interested in publishing, which is fantastic. Up Up by Mpho Mogkadi is an interesting example of young publishing in Joburg. It focuses on Johannesburg architecture, which is very Art Deco mixed with some Brutalism… there’s a lot to explore there.

BK: Crossing Strangers is a book that was published in Japan by mnkpress an independent publishing project based in Tokyo. How did they become interested to publish a book on Johannesburg?

AB: I became acquainted with the founder of MNK Press, the inimitable Hideko Ono, in 2014. She contacted me to assist the Japanese photographer Sohei Nishino, who was to be in Johannesburg on a photography project for 6 weeks. Our relationship grew out of that project, and her genuine and thoughtful approach, not only to my work, but to photobook publishing in general.

BK: You show your work around the globe. Did the reactions on Crossing Strangers differ in Japan and South Africa? How?

AB: Reactions within the continent, both in South Africa, and in Nigeria, where I took the book for the Lagos Photo Festival, have been focussed on the practicalities of presenting young photography in photobook format. Often people within the arts world here have the impression that publishing is something that one does at a later stage of one’s career.

I received the first responses to the work from Tokyo Art Book Fair last year in Japan. Their reactions seemed to be a product of their not knowing much about Johannesburg. Their only impression of the city before Crossing Strangers was of Jacaranda trees!

One woman working there, on first meeting me, said, “You live in the most dangerous city in the world. How did you get here?”. But the work seems to have the power to effect a change in people’s understanding of the city, which is really gratifying. On seeing the first copies, she pulled me aside, and told me that she found the city “beautiful”. It was very special to hear from Harada-san, another documentary photographer that he keeps the book beside his bed. He told me that he opens it on occasion and “imagines [my] country”, that it “makes [him] feel like [he has] travelled in South Africa alone.” To hear that the work has been transporting or transformative is the highest compliment.

BK: Since our blog is about the changing visual representation of Africa as expressed through the medium of the photobook I wonder if there is a book, or more, that you really admire and could be included to the website (according to you)? Please explain why?

AB: There’s definitely more than one. I highly recommend Up Up: Stories of Johannesburg Highrises. The photobook not only showcases classic buildings in Johannesburg but also offers a a glimpse into contemporary urban life in South Africa. Santu Mofokeng’s Stories: Train Church is one my favourite buys this year. The series reminds of my school days when I use to commute from Orange Farm to Lenasia, where I schooled, it also highlights the experience of commuting (migrancy) and the pervasiveness of spirituality as Santu Mofokeng mentions in the book.

Crossing Strangers can be ordered at MNK Press

One thought on “Interview – Andile Buka”